It All Started With a Joke About Gremlins

How I Learned About the Death Rattle

My life has always leaned Lynchian. Not in the dream-sequence kind of way. More like someone laughs at the wrong part of a story and then asks if you want gum. Conversations loop. People monologue about the weather with too much intensity. There’s always a weird energy humming under the room, like someone left something open and no one knows what.

Someone tells a joke mid-crisis like it’s a reflex. People perform normalcy like it’s a group project no one wants to fail. That kind of vibe.

Hover just outside it. Say enough to pass. Nod when expected. Rarely be all the way there. It's a low-maintenance camouflage. Stay quiet. Stay alert. Stay out of reach.

We were in a hospital. That’s not the part I want to talk about. Or maybe it is, but not directly. The energy was already off, which meant it felt normal.

Someone made a Gremlins joke. I laughed, mostly because I couldn’t picture them watching Gremlins, even though I’ve known them forever. They said they loved movies, pulled out their phone, and started listing everything they’d seen this year like it was a dare. At some point, someone brought up Gene Hackman. Apparently all his movies hit streaming after he died, and no one could agree on what actually killed him. That turned into an argument. Not a loud one, just the kind that flattens a room into competing Google searches.

Phones came out. Everyone got weirdly invested in being right.

I pulled out my phone too, ready to prove someone wrong about Gene Hackman. But just as I was about to type, I paused.

There was a noise. Or something pretending to be one. Low. Wet. Uneven. A breath that didn’t sound like breathing. I don’t think it was really there. I think my brain was just trying to give shape to the static. That’s what happens when you grow up in a Lynchian world. Your mind starts offering up its own sound design.

Nothing in the room changed. Nobody looked up. The chairs squeaked. Someone opened a soda. The vending machine made a sound like a cough. Someone else smiled at a picture on their screen like it was brand new.

Their phones never left their hands. I stayed with the sound. Or whatever I imagined it was.

It all started with a joke about Gremlins.

And somehow I ended up learning what the end of a body sounds like when it hasn’t caught up with itself.

I didn’t know what to call it at first. Everyone else was still arguing about Gene Hackman’s death, phones in hand, looking for proof. I had mine open too, but I wasn’t looking up actors. I was already halfway into a Wikipedia hole about something else entirely.

Death rattle.

I don’t know what I thought I was doing.

But I followed it anyway.

Because it was easier than facing anything else in the room.

So what is a death rattle, really? Short version: it’s what happens when your body keeps breathing after you’ve mostly stopped being a person. Short version’s enough for most people. I didn’t stop there.

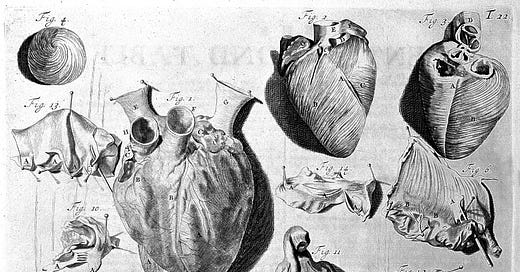

The clinical term is terminal respiratory secretions. It sounds like something you’d find in a pamphlet no one wants to pick up. The mechanics are simple. Toward the end, people lose the ability to swallow. Saliva and mucus start pooling in the back of the throat. The lungs keep working, but they’re pushing air through fluid now. That’s where the sound comes from. It’s not violent or dramatic. It just bubbles. It repeats. A rhythm the body forgot to turn off.

It doesn’t hurt. The person making the sound is usually unconscious. They don’t know it’s happening. But the people around them do. Because it doesn’t sound human anymore. It sounds like something mechanical. Something left on. Something that should have stopped, but didn’t.

Not everyone gets it. But a lot of people do. Somewhere between 40 and 70 percent of people experience it in their final hours, especially in hospice or home settings. It usually starts within the last day or two. There are drugs that can help, but they’re not for the person dying. They’re for everyone else in the room. The sound doesn’t bother the person making it. It bothers the people who are still pretending the moment might be beautiful.

The name "death rattle" started showing up in English medical texts in the 1700s. But the sound is older. It shows up in stories. In folklore. In the weird corners of religious texts. In Orthodox Christianity, it meant the soul was preparing to leave. In parts of Ireland, it was called the call, and people were told not to speak while it happened. Just listen. Let it pass. Some believed it was the soul trying to leave. Others thought it was death itself, breathing through the lungs as it entered.

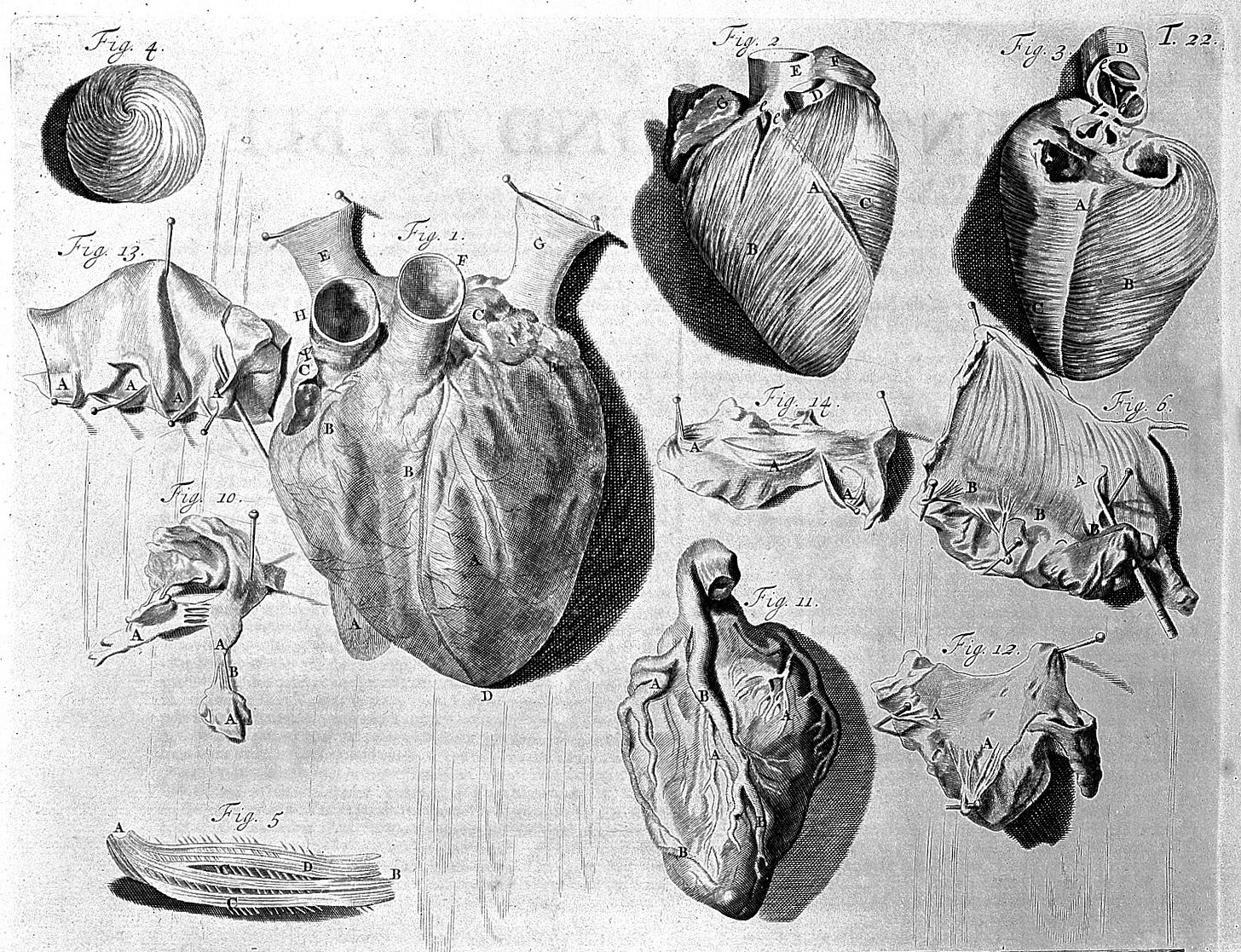

In Victorian homes, the death rattle had its own choreography. Curtains drawn. Mirrors covered. The priest summoned. The sound wasn’t symbolic. It was a cue. It told everyone to start acting like it was already over, even if it technically wasn’t. The person wasn’t gone, but they weren’t fully there either. The rattle sat in that in-between space. A breath pretending to still belong to someone.

These days, we mostly pretend it doesn’t exist. You don’t see it on television. You don’t hear it in films. It doesn’t test well. It doesn’t fit the version of death we like. We want final words. Something poetic. A quiet, graceful fade. Not a wet, rattling echo that sounds like it came from somewhere between the lungs and the crawlspace.

We’re trained to hear signals. A ding means food is ready. A buzz means someone wants your attention. Every sound in our day has a job. A function. Even silence gets used like a tool. But the death rattle isn’t a signal. It doesn’t tell you what to do. It just shows up, does its thing, and refuses to explain itself. It’s not trying to be noticed. It just is. And maybe that’s what makes it worse.

That’s what stuck with me. Not the sound itself. The fact that it has been happening forever and we still don’t know what to do with it. It doesn’t say anything. But it’s impossible to ignore.

Eventually I closed the tab. Put my phone down. The room was still doing what it does. Someone was explaining an office experience they had. Someone else said something too loudly, then looked around like they weren’t sure why. The lights were too bright. The corners felt too quiet. A chair squeaked again, exactly the way it had before. I watched someone scroll through Twitter while a monitor beeped nearby like punctuation no one had asked for.

Someone asked if anyone wanted snacks.

The noise was still happening.

They were already halfway to the vending machine.

It felt like I’d never left. Like I’d been there the whole time. Like I’d been watching myself sit in the same chair, nodding along to the same sentence, waiting for a different version of silence.

I don’t chase these facts because they help. I think I just like when something refuses to explain itself.

I’m not sure why I looked it up. Or why I’m writing about it now.

But maybe I’ll keep it in the back of my head while working on this book I only give hints about.

You never know when you're gonna need a sound that means nothing, happens once, and echoes forever...