Containment Was the Point

On Midwest Rot, Gender, and Institutional Silence

On the last episode of Textual Healing, Lake Markham mentioned that he was considering writing a book about the CTA. Not sure if I cut this part out of the episode or not because it turns into a pretty long tangent, but I told him that if he wanted to dig into Chicago history like that, the Newberry Library was a good place to start. It’s an independent archive of all things Chicago: labor records, reform notes, literature, art, correspondence, court cases, institutional magazines, and administrative forms. Basically, the paperwork of how the city built itself.

Several years ago, I spent time there doing a research fellowship focused on gender and labor in early twentieth-century Chicago. Sitting with those scans of archives with stale coffee on the cold first floor because coffee wasn’t allowed upstairs, certain patterns become hard to ignore. Not functions, but rituals. Habits. Not moments of crisis, but the systems designed to keep crises from becoming visible. Reading across labor disputes, reform efforts, and moral campaigns, the same priorities repeat: order, respectability, cohesion.

This is the point where it stopped feeling distant to me.

Rot and harm are present, but they’re softened through semantics. Conflict is deflected into what society considered decency.

Stability is protected by teaching people what not to name, and the people who are expected to carry that silence.

A labor report from the period I studied while at the Newberry describes a woman injured on the factory floor as having experienced “temporary nervous distress, resolved through improved domestic circumstances.” The incident is not categorized as injury or negligence. It’s treated as misalignment.

I didn’t jot any notes down the first time I read that. Just sat there a beat, shook in a way that words couldn’t yet describe.

The Midwest was fluent in what could only be described as sentimentalism and it sure as fuck wasn’t subtle. Male speakers regularly invoked gray-haired mothers and weeping widows in orations at Bughouse Square while opposing women’s political agency. Womanhood was honored as a symbol while actual women as workers or intellectuals were brushed aside.

I’m sitting in my office listening to Pat The Bunny while considering the irony of it all.

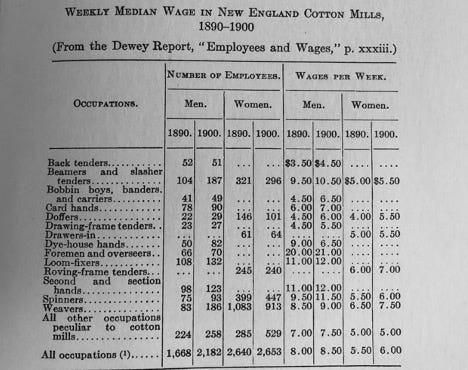

The Midwest waxed poetic about the “Mother.” A figure that was romanticized far before the time of Norman Bates. But for all its pontification, the region had far less interest in what actual women had to say. Devoted to this archetype, the Midwest offered its very last drops of blood to defend an ideal of domestic purity, so long as the actual women in the factories stayed quiet about the vulgar remarks and routine abuse that kept those factories running. They were meant to behave like cogs in a machine. Silent, stable, and always replaceable.

This is where what I now call Midwest rot becomes legible.

I didn’t have the language to describe it when I first saw it but I do now. To be legit, I’ve been staring at this draft for three days, trying to figure out how to tell you that the politeness of your neighbors was actually engineered by a 19th-century railway board.

I’ve written about Midwest rot before as emotion and design. Silence, repetition, endurance, the hum of anxiety in places where nothing ever happens. What I haven’t done yet was trace where those patterns came from. This isn’t a departure from that writing. It’s the source of it. What created the vibe. The system that taught silence to feel like stability, and endurance to feel like virtue, before it ever hardened into the culture that I speak about today.

The Midwest was organized this way to solve a distinct problem: how to make an expansive interior region of the country economically productive without constant instability. Unlike coastal cities built around trade, immigration, and change, the Midwest was shaped around land use, production, and steady labor. Farms, factories, rail road towns, and manufacturing centers required people to stay long enough to be reliable. Mobility threatened economic growth. Conflict threatened investment. Stability wasn’t just desirable. It was key to keeping the region’s economic model to function.

This logic was rarely spelled out but everyone seemed to know it.

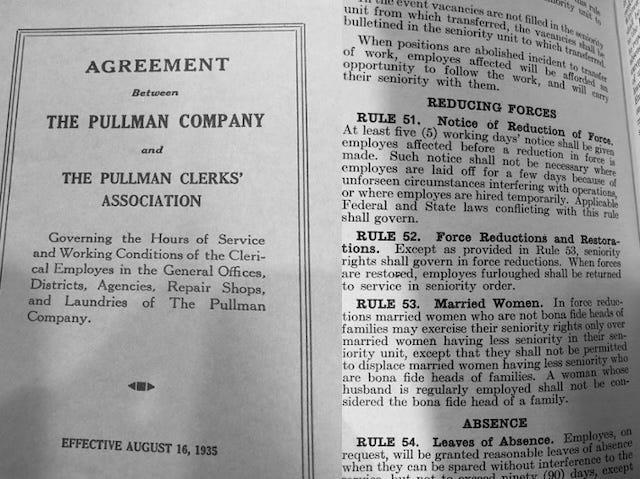

To achieve that stability, the Midwest relied on systems that rewarded permanence and punished disruption. They operated like a bubble. Land ownership, employment, church membership, and reputation were all tightly linked. To belong was to be comprehensible. To remain respected as a human being was to remain housed, employable, and socially protected. Institutions reinforced this logic by treating disorder as a personal failing rather than a structural outcome. The goal wasn’t to eliminate harm, but to keep it from interrupting the appearance of order.

Writing this with loud anarchist punk playing in the background somehow feels wrong given how much of this history depends on quiet.

Land ownership tied families to specific plots. Jobs were local. Leaving meant abandoning not just work, but community, reputation, and safety nets. Mobility was not encouraged. It was treated as instability.

Reputation functioned as currency. This is legit. A man’s standing determined whether a shop remained open, a farm stayed secure, or a town remained intact. To damage that standing was to threaten the economic unit itself.

In the Midwest, a man’s reputation was a public utility, while a woman’s trauma was a private liability.

This wasn’t controversial. Saying not much has changed might be.

I saw this logic everywhere in the archive. Men could violate stated principles and remain inside the movement. Women could uphold every rule and still be treated as expendable. Reputation was elastic if you owned something people depended on.

For a woman to name harm was to threaten the town’s stability. Midwest rot is the smell of a community choosing a predator’s standing over a victim’s safety because the predator owns the mill and the mill keeps the town alive.

Settlement didn’t mean stillness alone. It required constant maintenance. Homes had to be kept respectable. Reputations had to be preserved. Conflict had to be softened before it became visible. This work was not evenly distributed. From the start, the Midwest relied on a gendered division of labor that positioned women as the managers of stability itself.

This was a mood and no one needed to say it out loud.

Women were expected to absorb strain without externalizing it. You see this everywhere once you start noticing it. Like when you drive a specific car and then suddenly you see it everywhere you go. Women being the carriers of stability was all over the road. In court transcripts. Intake notes. Letters to editors. In the way harm is always directed through the household instead of the institution in which it exists.

To translate economic danger, workplace injury, and institutional neglect into domestic order, moral instruction, and emotional continuity. The system didn’t function despite this labor. It functioned because of it. Containment wasn’t incidental to women’s roles here. It was THE role.

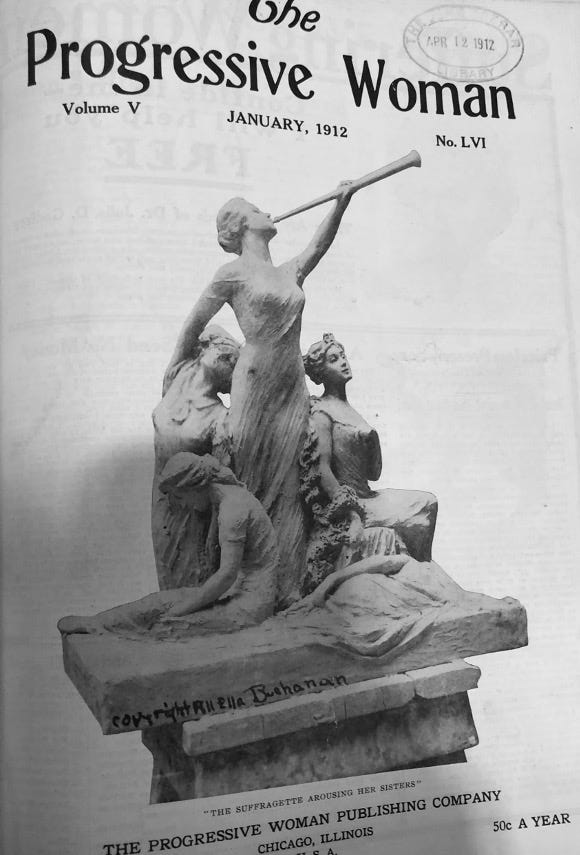

Of course, women didn’t accept this arrangement passively. They organized. They built resistance. They fought for reform across labor, public health, education, and social welfare. Early twentieth-century Chicago history is full of examples of women-led efforts aimed at alleviating exploitation, injury, and poverty. These movements mattered. They improved conditions. They saved lives.

But they operated within narrow constraints.

This was THE sentence that finally made the rules clear.

Reform literature from the period often praised women’s organizing work for its “ability to correct excesses without disturbing the harmony of the community.”

Women were encouraged to work, organize, educate, and stabilize, so long as they did it like housekeeping and not like architecture.

The approval is conditional. Reform is acceptable only if it does not interrupt the system it serves.

Women were invited to be the region’s janitors, but never its architects.

They were permitted to reduce strain and domestic circumstances, but the moment they pointed to the structural rot of the stage they were allowed to stand on, they were told the room was no longer fit for them.

In smudged court records and social work correspondence, women appear less as complainants than as intermediaries. Injury is reframed as household instability. Wage theft becomes marital strain. Institutional failure is translated into moral instruction.

Reading women writing to other women a century ago, I kept thinking: they knew exactly what they were up against. What they didn’t have was permission to say it plainly.

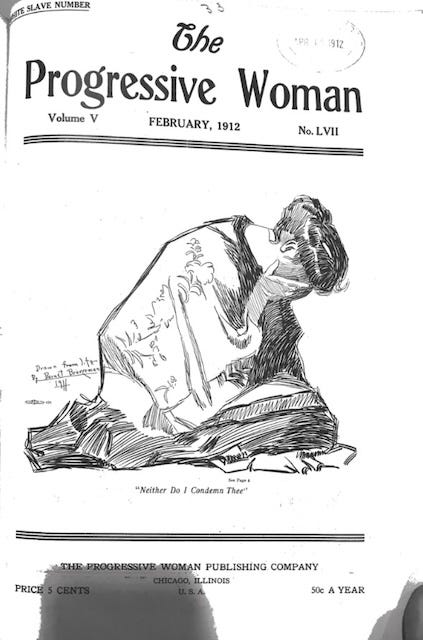

The language available to women mattered. When harm couldn’t be named, it couldn’t be argued. What was felt was described instead as misfortune or personal failing.

Over and over, women described experiences everyone recognized without ever being allowed to name them. Harassment became misfortune. Coercion became temptation. Survival became moral failure.

The rot grows in the gap between what is felt and what is sayable. When a workforce experiences unspeakable suggestions but calls it misfortune, the system has succeeded in making the victim the curator of her own silence.

Women everywhere were asked to absorb harm. That isn’t the distinction. The distinction is how that absorption was structured, permitted, or resisted.

Other regions offered outlets for conflict, hierarchy, or exit. The Midwest offered endurance. It stored harm instead of metabolizing it.

On the East Coast, density and proximity made confrontation unavoidable. Women organized publicly, argued openly, litigated, protested, and wrote polemically. Speaking carried risk, but it did not automatically sever belonging. Conflict was an expected part of civic life, even when it was punished.

In the South, women’s containment was enforced through explicit hierarchy. Power was visible and brutal. Silence was not moralized as virtue. It was coerced. Harm was not hidden behind respectability. It was maintained through threat, violence, and law. Women’s endurance was demanded, not praised.

In the West, mobility offered a partial release. When gendered expectations became intolerable, leaving was culturally intelligible. Reinvention functioned as pressure relief. Women could exit communities that refused to change, even if that exit carried economic and personal cost.

The Midwest offered none of these mechanisms. Open conflict threatened cohesion. Explicit hierarchy contradicted the region’s self-image of decency. Exit undermined the labor stability the economy depended on. What remained was containment.

Here, women weren’t encouraged to confront harm, flee it, or name it openly. They were trained to absorb it quietly. Endurance was framed as maturity. Silence was framed as strength. Holding things together was proof of moral character.

Midwest women weren’t uniquely passive or uniquely strong. They were positioned inside a system that required harm to be stored rather than released. Their labor was not resistance or submission alone.

Over time, that stabilization hardened into the culture we know today.

The institutions that produced this training have shifted or faded into history. Factories closed. Reform movements professionalized. Laws adopted new language. But the rituals remain. The silence outlived the structures that built it.

What was once enforced institutionally now appears as temperament. Endurance reads as maturity. Not making trouble reads as maturity. Women learn early which complaints will be read as legitimate and which will be treated as interference. They learn how to translate harm into something manageable. Something polite. Something that won’t follow them.

This isn’t inherited memory so much as inherited posture. The instinct to soften a story before telling it. The reflex to explain suffering in ways that protect other people’s comfort. The sense that naming something too clearly will make you the problem.

In the Midwest, this still passes for stability.

Workplaces reward the person who absorbs strain without complaint. Families praise the daughter who keeps her shit together. Communities respect quiet tolerance more than truth-telling. Conflict is still treated as a character flaw. Reputation still functions as worth. Silence still protects the system.

What’s changed isn’t the logic, but the scale. The harm is more scattered now. Less legible. Harder to point a finger at. But the demand remains the same. Don’t escalate. Don’t accuse. Don’t shatter the silence that was keeping the room still.

Midwest rot isn’t nostalgia or vibes. It’s the afterlife of this grooming. The unending twinge that something is wrong, paired with the certainty that saying so would only make things worse. The anxiety that comes from carrying too much without being allowed to throw it down.

Once you see the history of the system that produced it, the rot stops feeling ethereal. It feels familiar. Personal. Like something you were taught long before you knew you were being taught anything at all.